Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Maybe the GMOs Made Me Write This

I’m really tired this week. I am normally one of those annoyingly high energy, naturally caffeinated people who functions well on very little sleep. It’s just the way I was made, nothing that I can take credit for, I’m afraid. The past few weeks have been hard, though, and I feel like taking a nap every time I go online. It’s emotional exhaustion that I feel. More than anything, it’s a bone-tiredness that comes from feeling like even the most innocuous things I see people post are subject to hyper-critical and personal attacks.

I often try to imagine how things would look if we talked to one another face-to-face the way people talk to each other on social media platforms and in comment threads. For example, what if I just walked up to someone in a grocery store, poked through the contents of her shopping cart and talked to her like people often do on Facebook? I might say, “Why are you buying bread? Don’t you know what gluten does to your healthy gut bacteria? Destroys it. You’re probably in a mental fog, though, so you wouldn’t know that. You should get the Mercola updates. And what about that frozen corn? Is it organic? If it’s not organic, it’s GMO and if you eat it, you’ve just become a walking toxic dump. Monsanto owns you. I hope you don’t have children. You do? Ah, yes, another stupid breeder. Well, maybe things will work out and they’ll all be infertile. Otherwise, I give up...”

Yet this is exactly how so many people behave online, often around food issues: With shouting, finger pointing, insults and condescension. There seems to be no regard for how people actually need to communicate in order to be heard. I know that I am stating the obvious here but I see this behavior so often I have to wonder if technology has just ushered in another lower level of incivility. We have so much more access to one another now, to perfect strangers from around the world, and what do we choose to say to each other? How do we communicate? So often, we are rude and callous.

It’s my experience that self-appointed food custodians are among the most abrasive. In my case, I am a supporter of organic, local and independent growers and I have been since the 1990s, when my husband and I signed up a members of this novel (to us) endeavor called Community-Supported Agriculture. We were early members of this particular pioneering CSA. This was before the internet, and John and I would huddle together, squinting at the Moosewood-inspired illustrated newsletter that came with every heady box, trying to figure out what to do with escarole. (“Sauté with garlic! Then sip blueberry juice and twirl in the moonlight.”) Before there were marches against Monsanto and so on, my husband and I protested industry conferences, we staged poignant monarch butterfly die-off street theater (one ended up in the Washington Post) and co-founded Chicago’s first anti-biotech group. In fact, deep concerns about biotechnology and corporate domination informed my first novel. So I get it, I really do.

That being said, I have seen all kinds of really outlandish claims about genetically engineered foods on social media, enough to make Area 51 conspiracy theorists look fairly reasonable and measured in comparison. I have seen people speculate that Monsanto was responsible for the September 11th attacks; I have seen every clip-art generated variation of crossbones with ears of corn that could be conceived. Again, I get it. I understand the concerns and I share them. In other words, no one needs to lecture me. Yet I get called out repeatedly by people who seem to believe that all soy that is grown is pulsing with radioactive GMOs and every kernel of corn is embedded with identity-stealing nanotechnology. Why do I get the sense that every time I share a recipe, there is a line of people ready to start tapping as soon as it appears on their screens, eager to scan the ingredients and be the first to out it as a potential source of GMOOOOOOOs?

This is just to ask if we can’t give one another just a little benefit of the doubt. Before you want to edify someone about their toxic diet, perhaps it’s better to take a breath, count to ten and ask yourself how you like to be talked to in life. It’s really not complicated stuff.

So when I say this, I say it with respect and a feeling of kinship: food activists on social media, for the love of all that is good in the world, could you please chill the out? Pretty please? Take some non-irradiated valerian supplements. Cut down on the green matcha lattes. Do something. I say this because not every picture of food that is posted needs to be swiftly identified lest all viewers of said photo risk exposure to a pernicious case of genetically engineered eye cooties and most people don’t like to be talked to like they are complete morons.

Again, I’m just really tired. (Or maybe it's just all those GMOs.)

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

The Trauma of Knowing: A Cracked Vessel Will Eventually Run Dry

“When the well is dry, we know the worth of water.” Benjamin Franklin

About a year after I went vegan and became an activist, I watched a film that took me to my emotional brink. It was a collection of short undercover videos taken of elephants being trained for circuses and as rides for tourists eager to cross items off their bucket lists throughout Asia. The word “trained” is a euphemism for “broken.” The process of breaking an elephant is devastating to see; babies and adolescents, stolen from their mothers or orphaned, are tied up or held captive in tight cages and beaten again and again until they stop resisting and become submissive. As adults, many are routinely smacked with bullhooks to get the elephants to move and keep them tractable. The practice of putting these sensitive beings through sustained beatings and abuse is called “elephant crushing,” and appropriately so: their spirits are indeed crushed in the process of making them docile and compliant enough to be safe among the public. As they are crushed, they cry just like human babies do and they cower just as anyone who has been beaten around the clock would cower. At the end, they are broken, just husks of who they could be, passively swaying in place and bobbing their heads in captivity.

I knew about the practice of breaking elephants and had been telling people about it but watching the footage made it a much more visceral and piercing experience. We can intellectually understand these things, and be genuinely upset, but seeing it with our own eyes further erodes the walls of detachment, making the violence both real and immediate. Watching the footage, merely 15 minutes altogether, made me shake uncontrollably and collapse to the floor in tears; even as it was happening, it was as though I could also see myself as a stranger, gutturally weeping and gathered in a fetal position, from a set of eyes separate from mine: Who was this person? Was this me? Yes, and I was on the edge of a nervous breakdown. I was dissociating. John tried to turn off the VCR but I insisted on watching the rest, curled up on the floor, raging through my tears. If the elephants had to go through this torture, the very least I could do was bear witness.

For two weeks afterward, I was in a state of emotional and physical shock from watching and viscerally feeling the abuse of those animals. I couldn’t sleep or eat. I felt like I was always partially absent, in a dream-like state, on the verge of being startled all the time. I couldn’t talk to anyone above a whisper, which made work difficult. When I wasn’t numb, I cried and cried and cried until I was worried that I’d burst a capillary. (Being numb was worse, though.) More than anything, I wanted to remove myself from society, from these horrible people, from those who didn’t give a damn about anything. As I sat awake in the dark every night, I fantasized about digging the world’s biggest moat around our house and never having to face the anyone else again outside of my husband and dogs. I was furious at humankind.

Slowly, bit by bit, I began to return to myself again. I made it through one hour, then two hours, then a whole afternoon, without flashing back on those images, without hearing their tormented cries, without crying in the bathroom stall. I was still at a crossroads, though: Do I immerse myself in bearing witness or do I concentrate on being effective? Because through this experience, I realized that I couldn’t do both.

It’s vital to know what we’re talking about, and in communication, it’s also important to not be robotic, to speak in a way that conveys in a way that resonates what the animals face as they are turned into entertainment, research subjects, what people eat. This is a conundrum, though, because, at least for me, I couldn’t expose myself to the horrors without breaking down and either becoming numb or overloaded with despair. If I am emotionally paralyzed or deluged, how can I be a compelling advocate on behalf of the animals? On the other hand, isn’t it cowardly to not even be able to watch what they have faced? Doesn’t seeing what they endure make me a more effective communicator, too?

Yes and no. The answer for me was to indeed bear witness but also respect my boundaries of when I’d reached that point of feeling it deep-down but not so much that I was flooded, drowning in a state of despondency. As advocates, we need to be in this for the long haul. The animals need us for this, too. We are their bridge to the public. We are serving no one - not the animals, not ourselves - if we become so emotionally devastated that we cannot communicate effectively.

I see activists succumb to burnout all the time because they don’t think they deserve a little consideration for their own wellness. It is something akin to survivor’s guilt: if the animals go through what they do, the least I can do is bear witness. They punish themselves with horrific videos, with immersing themselves in misery, with the mistaken notion that by doing so, they are at least doing something. A wise person told me something, though, that will always stick with me: There is no pain that I can inflict upon myself, no grief that I can grieve, that will lessen the pain and grief of another. We cannot be someone else’s emotional proxy. We can be empathetic. We can speak out against what is done to the animals. We can take action. We cannot lessen their suffering, though, by suffering ourselves; in fact, we can very much fail them if we quit due to being overwhelmed. I could have quit, too, right then all those years ago. There is nothing that animal abusers would love for us to do more than give up doing what we’re doing and remain silent and immobilized in our little corners of the world.

I am not going to give them that satisfaction, though. I am never going to bow out. I am here for the rest of my life and I will ensure that by taking care of myself. So here are some little things you can do to maintain your emotional and mental health: Laugh a little. Exercise. Garden. Cultivate other interests. Go for a bike ride. Play volleyball. Take the sweetest dog you know on a walk in the woods. Take a pottery class. Meet a friend for dinner. Take a mental health day. Hula hoop. I promise no animals will be harmed because you allowed yourself some enjoyment. I promise. I can also guarantee you that taking care of yourself means that you will have more to give others, too. Plus, you deserve happiness for your own reasons, just like any other being.

Respect your own boundaries the way that you would want someone else to respect them and trust yourself to know when you have seen enough. For me, a little goes a long way. I know this now. For others, watching the violent footage truly does fuel their activism and they don’t get too overloaded. There are benefits to seeing it and benefits to protecting your heart. Find a balance that works for you. Again, if you burn out due to emotional exhaustion, there is no benefit to anyone.

Be gentle with yourself because this is brutal stuff we’re excavating for others to see and we desperately need you here for the long haul.

Wednesday, May 14, 2014

On Blinders and Everyday Atrocities....

“The trouble is that once you see it, you can't un-see it. And once you've seen it, keeping quiet, saying nothing, becomes as political an act as speaking out. There's no innocence. Either way, you're accountable.” - Arundhati Roy

Last week, without even searching for it, I learned about yet another routine horror that is inflicted upon the animals that we eat.

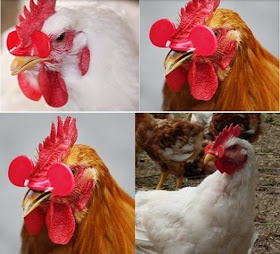

The birds in this photo are wearing something called “blinders” or “peepers,” which are especially treasured among backyard chicken enthusiasts as a way to keep these naturally territorial animals from plucking out one another’s feathers or cannibalizing each other due to the stress of captivity. (Blinders are not typically used in more intensive confinement operations because it is most time- and cost-efficient to routinely de-beak the birds to limit the expense of aggression on the business’s bottom line.) The blinders, pierced with a pin through the nasal septum or, with the pinless variety, affixed to the nostrils with prongs using a special pliers, block the vision of the bird, as well as interfere with eating, drinking, and natural behaviors like preening; both versions are also damaging to the chicken’s nostrils and beak. (By the way, if you want to see how genuinely at least one backyard chicken enthusiast cares about the animals in his or her care, you might want to see this; reading the description of how the blinders were fitted to the chicken, the nonchalant, mocking recounting of the bird’s distress, and the cruel “joke” this wannabe urban homesteader played on the now visually obstructed bird, we get a lens into the glacial sadism that underpins this individual’s hobby.)

I first heard about these blinders in a round-about way. I shared a meme we’d created and a woman commented on the thread, mentioning a rooster named Victor who managed to be rescued after he fell off a slaughterhouse-bound transport truck and had this horrible devise pierced through his delicate nasal passages. Imagine his disorientation and fear, not only being surrounded by other stressed birds but having his vision blocked after he fell off a truck. Fortunately for him, a compassionate person found Victor and he was taken to Full Circle Farm Sanctuary in North Carolina, an oasis where he lived out the rest of his days in peace and as much comfort as could be provided given what had already been done to him, finally having had the blinders removed by a veterinarian. Victor was truly a rare bird, much more of a statistical improbability than a lottery winner.

I’ve been off animal products since February 1, 1995, and part of my early education as a new vegan centered around learning about the multitude of strategies agribusiness has developed to make it easier and more profitable to dominate the animals who are eventually consume. I’ve long known about forced impregnations and castrations without anesthesia or follow-up care, about formula-fed calves and male chicks killed at birth, but through the process of researching and creating our weekday memes for Vegan Street, which my husband and I revitalized last July after more than a decade of dormancy, we have learned about so much more. It turns out that what I knew about was really the proverbial tip of the iceberg; just when I think that I can no longer be stunned by this industry’s capacity to engineer truly sadistic devices and practices, pervasive on both large-scale and small-scale enterprises, I learn that I was mistaken. There is more, much more. Nearly every week, I learn about these things, from dairy huts to dead piglets being fed back to their mothers, from weaning rings to, now, blinders. By this point I know that there will probably be no shortage of occasions to be thunderstruck by the true depravity and chillingly rote methodology of the animal agriculture industry as it continues to supply a steady quantity of flesh and animal products to meet consumer demand.

I’ve learned that for virtually every part and function of the animal that could interfere with flesh, dairy or egg production or profits (they are virtually interchangeable), we have devices designed to frustrate, minimize or remove those “impediments.” Declawing, dehorning, and tail docking done as a matter of course, to name a few more things, and there are also barbaric practices to make the animals easier to identify and control, such as ear notching, branding, and nose ringing. Snoods, toes, wing joints and more are forcibly removed as standard practice, again, without anesthesia and without follow-up care, to reduce damage, hardship or financial risk to the operation’s bottom line. They are our living products, kept alive until they are worth more dead.

There are entire, robust industries that have emerged to facilitate turning these sensitive beings into products as quickly, easily and efficiently as possible. As I research more, I am in a constant state of bracing myself as the hidden underbelly of agribusiness emerges and as we work to expose people to what happens behind the heavy curtains. Once in a while and with a great deal of effort, the curtains are parted just a little bit and a tiny percentage of the public can see a small bit of what is happening. As we are peeling back the curtain, what we see is every bit as atrocious as could be expected.

Actual blinders are used on chickens and metaphoric ones are used by people on ourselves when we can’t face the consequences of our habits. These are the everyday atrocities we agree to when we eat animals, whether they were done with our own hands or someone else’s hands. Make no mistake, though: the atrocities are happening because of us and, as Arundhati Roy said, once we know, we are accountable whether we act or we don’t. There is no innocence. You can’t un-see what you’ve seen. Take off all the blinders. The atrocities can end because of us, too.

Wednesday, May 7, 2014

Snappy Retorts, Part Two: Hitler's Humane Teeth

“Really? That’s not what the historian Rynn Berry found. Also, even if he had been a vegetarian, how is this relevant to me? I’m a vegan, not a vegetarian.”

“So you’re saying that even for the individual who most personifies evil, eating animals was too barbaric? What does that say about eating animals?”

“So were Josef Stalin, Pol Pot, Idi Amin and Mao Zedong. Oh, wait. No, they weren’t. Oops. I’m sorry: what were you saying again?”

“Because having empathy for the billions of sensitive beings killed each year to maintain our habits is clearly consistent with being one of history’s most horrific killers, right?”

“Yes, of course. His ideology was outlined in his manifesto, ‘Mein Kale.’ That will always haunt the vegan community.”

“Well, it’s certainly very reasonable to think that we can acquire the flesh of another being through humane means. Oh, look! A sparkly unicorn frolicking with a leprechaun!”

“I’m sure those animals you will eat are very thankful that their throats will be unnecessarily slashed with loving-kindness rather than violence. How sweet.”

“Is it hard to eat when you have to stop and pat yourself on the back all the time?”

“How is it that ‘humane meat‘ is only about one percent of what is produced in the United States but every meat-eater I know claims to only eat that kind? How is that possible? Do you guys have an exclusive buying club or something?”

“I humane mugged someone today on my way to humane robbing the local charity so I totally get what you’re saying.”

“Those little, slightly pointy teeth? Yes, those will certainly strike fear and dread in the hearts of all the zebras you encounter.”

“Those so-called canine teeth are also found on herbivorous animals and used to chew tougher fiber. But if you want to imagine that you’re a big, tough lion of the Serengeti, that’s up to you.”

“So you supposedly have these fearsome canine teeth but you lack large paws, sharp claws, a massive jaw and the ability to outrun your prey? You sound pretty bad ass.”

“So one possible explanation for how you turned out is that instead of putting all that energy into maximizing your brain power, your body decided to invest in developing those ‘terrifying’ canine teeth of yours instead? It seems like a bit of a lose-lose, but whatever.”

“Dracula called. He thinks you’re a poser.”